While climbing has never been so popular, the number of routes in the wild is increasing. Clean climbing aims to raise awareness of the consequences of this expansion and to limit its harmful effects.

A few months after its first time at the Olympic Games in TokyoClimbing takes full advantage of this mondovision visibility. Every year, more and more people come to get a taste of the discipline in the climbing gyms or try their first route outdoors. But if the Olympics were a gas pedal, the trend is not new and has been going on for over 20 years now. According to the FFME (Fédération Française de la Montagne et de l'Escalade), the number of licensed climbers in France has risen from 50,000 in 2002 to over 100,000 today. This figure does not include the unlicensed amateurs who climb all over the place on artificial and natural routes.

As a direct consequence of this expansion, the number of spots has multiplied, and with it, the number of routes. Outdoors, some climbers have long been aware of the impact their sport can have on the environment. Clean climbing was initiated almost 50 years ago by Anglo-Saxon climbers such as Royal Robbins, Doug Robinson, Tom Frost and Yvon Chouinard. In the 1970s, these climbers tried to switch from pitons to belayers in order to protect the rock.

Climber and manufacturer Yvon Chouinard (founder of Patagonia) went a step further, proposing new climbing equipment in his 1972 Chouinard Equipment Catalogue, designed to meet this goal of protecting nature. "The fewer gadgets between the climber and the climb, the greater the chance of achieving the desired communication with oneself - and with nature," explains Yvon Chouinard.

"Clean climbing is mitigation of adverse effects. But mitigation isn't sexy, it's having to accept reality," says Mailee Hung in an article on the subject published on Patagonia website. "For some, this very acceptance is tantamount to admitting failure. The reality of our humanity, the simple fact that everything we touch bears our marks, is a failure. Clean climbing recognizes this reality and urges us to pay attention to the traces we leave behind. This philosophy is reflected, for example, in the film "Les emmerdeurs" (below), in which we discover the work carried out by climbers and ecologists at the Claret cliff, a well-known climbing spot near Montpellier.

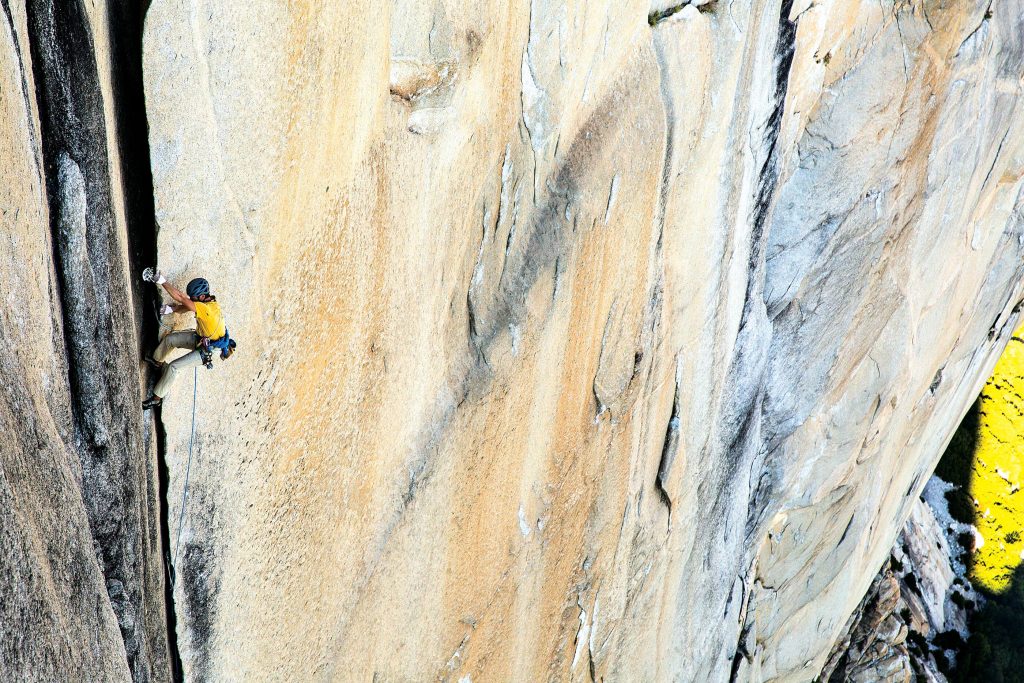

On the professional side, clean climbing is echoed by some like Sean Villanueva, Patagonia climber, whose brand continues to support this movement. "I first discovered clean climbing when I climbed in Ireland while on vacation with relatives. Back then, there were no studs in Ireland: you could look at a wall with climbing routes, without seeing any equipment in place, any scars or human impact. There's something beautiful about accepting rock as it is, even if it's sometimes impossible to climb. It's not that we've never or will never use a dowel, but it's something we don't take lightly. If a climb isn't possible for us without a dowel, and we feel it's unwise to put one in, then we turn back."

"When Nicolas Favresse and I left for Greenland, we didn't know what we were going to do or what we were going to climb. Crossing the Atlantic under sail was part of that experience. As soon as we landed on this wild and isolated fjord on the east coast of Greenland, it became our home for a month and a half, with unlimited possibilities. Spires, mountains and glaciers as far as the eye could see. It makes perfect sense to leave these areas as wild as possible, because that's the very reason we love going there. On the 8 new routes we climbed, we didn't place a single stud or piton. We left on foot without leaving anything behind whenever we could."